Notes on Advent of Code 2024

I'm making this a tradition, as I wrote about Advent of Code during the past couple of years. This is the 10th year of Advent of Code!

All my solutions are on my GitHub here. Any the standard disclaimer:

Disclaimer on my solutions

I use Python because I find it easiest for this type of coding. I treat solving these as a write-only exercise. I do it for the problem-solving bit, so I don't comment the code & once I find the solution I consider it done - I don’t revisit and try to optimize even though sometimes I strongly feel like there is a better solution. I don't even share code between part 1 and part 2 - once part 1 is solved, I copy/paste the solution and change it to solve part 2, so each can be run independently. I also rarely use libraries, and when I do it's some standard ones like

re,itertools, ormath. The code has no comments and is littered with magic numbers and strange variable names. This is not how I usually code, rather my decadent holiday indulgence. I wasn't thinking I will end up writing a blog post discussing my solutions so I would like to apologize for the code being hard to read.

I won't cover the first few days, as the first problems are always easy. The first fun one for me this year has been part 2 of Day 12:

Day 12: Garden Groups

Problem statement is here.

Part 1 was easy. I used a recursive algorithm like flood-fill to find the area and perimeter of each garden. Keeping track of the squares already visited, we add 1 to the area for this square then, if the north, east, south, or west square has the same letter as the current one, we visit it recursively, otherwise we add 1 to the perimeter (as we encountered a wall).

Part 2 was more interesting: we need to identify the number of sides rather than

the perimeter. A side is any contiguous boundary that can span multiple squares.

I tried to come up with the simplest way to tell how many sides an area has and

here is what I got: the number of sides is equal to the number of corners

, so

rather than counting sides, we can count how many times the the boundary takes a

corner.

For north-west, we have two cases in which we have a corner:

XX XA

XA AA

If our square is A, if both north and sound are not A, we have a corner.

Alternately, if both north and west are A but north west is not, we also

have a corner.

All other permutations have the north east point be part of a segment or within the area, not a corner:

AA XA XX

AA XA AA

With this, we can compute how many of the four points around a square are corners. Retrofitting this to the part 1 flood-fill algorithm, we can get, for each area, the total surface and total number of corners.

Day 13: Claw Contraption

Problem statement is here.

Part 1 was easy to brute-force, given the at most 100 moves

constraint.

Part 2 can't be brute-forced. That said, the solution is very straight-forward:

\[ \left\{ \begin{aligned} &X_A * i + X_B * j = X_{target} \\ &Y_A * i + Y_B * j = Y_{target} \end{aligned} \right. \]

Here, \(X_A\) and \(Y_A\) are the X and Y offsets we get when pressing button A, while \(X_B\) and \(Y_B\) are the offsets when pressing button B. Our target coordinates are at \(X_{target}\) and \(Y_{target}\). So we just need to solve for \(i\) and \(j\).

Day 14: Restroom Redoubt

Problem statement is here.

Part 1 was again easy, just simulate 100 moves for each robot and figure which quadrant they end up in.

Part 2 was surprising, I was expecting something like instead of 100 moves, simulate some million moves. I didn't really solve finding the easter egg algorithmically. Rather I advanced the robots step by step and displayed the results. I noticed they tend to cluster at certain steps - for my input it was 33, 136, 239 etc. They didn't quite form a picture but I figured I can just look at steps \(33 + n103\) to find the easter egg, and indeed after a number of iterations the robots formed a picture!

Day 15: Warehouse Woes

Problem statement is here.

Part 1 was very easy.

Part 2 was a bit more tedious. For pushing boxes around horizontally, same code as part 1 work, but for vertical pushes, we need to account for wider boxes. I implemented two functions for this, first one just tells us if a move is possible:

def can_move(i, j, d):

if grid[i + d][j] == ".":

return True

if grid[i + d][j] == "]":

return can_move(i + d, j - 1, d) and can_move(i + d, j, d)

if grid[i + d][j] == "[":

return can_move(i + d, j, d) and can_move(i + d, j + 1, d)

return False

can_move() recurses until it either finds a free . spot for everything that

needs pushing or until it hits a wall, in which case a move is not possible. The

d argument is the direction, since the only difference between going up and

down is whether we subtract 1 or add 1 to the row i.

If a move is possible, then we can update the grid like this:

def do_move(i, j, d):

if grid[i][j] == ".":

return

elif grid[i][j] == "[":

do_move(i + d, j, d)

do_move(i + d, j + 1, d)

grid[i + d][j], grid[i + d][j + 1] = "[", "]"

grid[i][j], grid[i][j + 1] = ".", "."

elif grid[i][j] == "]":

do_move(i + d, j - 1, d)

do_move(i + d, j, d)

grid[i + d][j - 1], grid[i + d][j] = "[", "]"

grid[i][j - 1], grid[i][j] = ".", "."

elif grid[i][j] == "@":

do_move(i + d, j, d)

grid[i + d][j] = "@"

grid[i][j] = "."

Not the most pretty but it does the job: if we're on an empty spot ., we stop.

Otherwise if we're on a half of a box, we recursively move up the row above (or

below), then shift the box and replace it with empty space. Only other option is

we're on the @, in which case we also shift it and replace it with empty

space.

Day 16: Reindeer Maze

Problem statement is here.

For the first part, I used a queue and kept track at each step of the best score found so far for the given coordinates + heading. At each step, we can move 1 square towards our heading or rotate 90 degrees, changing our heading. This will find the best score with which we can reach the destination.

s_i, s_j = len(grid) - 2, 1

e_i, e_j = 1, len(grid[0]) - 2

visited, best, queue = {}, 10 ** 9, [(s_i, s_j, "E", 0)]

while queue:

i, j, heading, score = queue.pop(0)

if grid[i][j] == "#":

continue

if (i, j, heading) in visited and visited[(i, j, heading)] <= score:

continue

visited[(i, j, heading)] = score

if i == e_i and j == e_j:

if score < best:

best = score

continue

match heading:

case "E":

queue.append((i, j, "N", score + 1000))

queue.append((i, j, "S", score + 1000))

queue.append((i, j + 1, heading, score + 1))

case "N":

queue.append((i, j, "W", score + 1000))

queue.append((i, j, "E", score + 1000))

queue.append((i - 1, j, heading, score + 1))

case "W":

queue.append((i, j, "N", score + 1000))

queue.append((i, j, "S", score + 1000))

queue.append((i, j - 1, heading, score + 1))

case "S":

queue.append((i, j, "W", score + 1000))

queue.append((i, j, "E", score + 1000))

queue.append((i + 1, j, heading, score + 1))

For part 2, my solution ended up quite long. I didn't want to update change the

traversal algorithm from part 1. Rather, I figured we can re-construct the best

paths starting from the end and looking at the visited squares we've been

keeping track of: if, for example, we are at coordinates i, j, and heading

"N" (north) with a score of S, then if the score we have for (i - 1, j,

"N") is S - 1, then the square at i - 1, j (with heading N) is also

part of the best path. Similarly, if (i, j, "E") or (i, j "W") had score S

- 1000, then turning is also part of the best path.

We already have all the scores in visted, so I reconstructed the best paths by

backtracking from the end:

path = set()

def backtrack(i, j, heading, score):

path.add((i, j))

if i == s_i and j == s_j and heading == "E" and score == 0:

return

match heading:

case "E":

if (i, j, "N") in visited and visited[(i, j, "N")] == score - 1000:

backtrack(i, j, "N", score - 1000)

if (i, j, "S") in visited and visited[(i, j, "S")] == score - 1000:

backtrack(i, j, "S", score - 1000)

if (i, j - 1, "E") in visited and visited[(i, j - 1, "E")] == score - 1:

backtrack(i, j - 1, "E", score - 1)

case "N":

if (i, j, "W") in visited and visited[(i, j, "W")] == score - 1000:

backtrack(i, j, "W", score - 1000)

if (i, j, "E") in visited and visited[(i, j, "E")] == score - 1000:

backtrack(i, j, "E", score - 1000)

if (i + 1, j, "N") in visited and visited[(i + 1, j, "N")] == score - 1:

backtrack(i + 1, j, "N", score - 1)

case "W":

if (i, j, "N") in visited and visited[(i, j, "N")] == score - 1000:

backtrack(i, j, "N", score - 1000)

if (i, j, "S") in visited and visited[(i, j, "S")] == score - 1000:

backtrack(i, j, "S", score - 1000)

if (i, j + 1, "W") in visited and visited[(i, j + 1, "W")] == score - 1:

backtrack(i, j + 1, "W", score - 1)

case "S":

if (i, j, "W") in visited and visited[(i, j, "W")] == score - 1000:

backtrack(i, j, "W", score - 1000)

if (i, j, "E") in visited and visited[(i, j, "E")] == score - 1000:

backtrack(i, j, "E", score - 1000)

if (i - 1, j, "S") in visited and visited[(i - 1, j, "S")] == score - 1:

backtrack(i - 1, j, "S", score - 1)

backtrack(e_i, e_j, best[0], best[1])

This is not the prettiest implementation but after running this, the length of

path gives us the solution. Some of this can be condensed: if we're heading

either "E" or "W", we can only change heading to "N" or "S" etc., but

GitHub Copilot was very good at filling in all the different cases, so I just

went with it.

Day 17: Chronospatial Computer

Problem statement is here.

The first part was easy, just simulate the machine and execute the instructions.

The second part was a lot more fun. It was clear it's too hard to brute-force, so I had to spend some time analyzing the program itself. For my input, it looked like this:

bst @A

bxl 1

cdv @B

bxc

bxl 4

adv 3

out @B

jnz 0

In other words:

B <- A % 8 (last 3 bits of A)

B <- B XOR 1

C <- A >> B

B <- B XOR C

B <- B XOR 4

A <- A >> 3 (right-shift A 3 bits)

OUT <- B % 8 (last 3 bits of B)

JNZ 0 (repeat until A is 0)

The key takeaways from this are:

- Each step consumes the last 3 bits of register A

- ...which means B is between 0 and 7

- ...which C is A right-shifted by at most 7 bits

- ...then B gets XORed with 4 and C

- ...and we print its last 3 bits

At most the last 10 bits of A are relevant to producing an output (since C is A right-shifted by at most 7 bits and XORed with B which comes out of the last 3 bits of A).

I implemented a function that takes a value of register A and prints the output after one iteration:

def step(a):

b = a % 8

b = b ^ 1

c = a // 2 ** b

b = b ^ c

b = b ^ 4

return b % 8

We search for the solution in groups of 3 bits:

- We find all permutations of 10 bits that produce the output number we want

- We prepend the last 3 bits to our solution

- We recursively look for the values that produce the next 3 bits but we keep the remaining 7 bits from this step as a suffix we expect the next iteration to have

So if we find that, say b1000101010 outputs the first number we want, 4, we

store the last 3 bits (010) as part of our solution but also expect numbers at

the next step to end with 1000101.

Once we find all numbers in the program this way, we make sure the suffix is 0 (we shouldn't be expecting more digits as we should terminate the program), and we found a solution. We can keep track of which of the solutions we found is the smallest one. The whole search function is here:

best = 10 ** 20

def search(i=0, valid_suffix=None, n=0):

global best

if i == len(prog):

if valid_suffix == 0:

best = min(best, n)

return

for x in range(1024):

if valid_suffix is not None and x & (2 ** 7 - 1) != valid_suffix:

continue

if step(x) == prog[i]:

search(i + 1, x >> 3, ((x % 8) << (3 * i)) + n)

prog contains the program instructions - the numbers we are searching for. If

we found all of them, valid_suffix should be 0, otherwise we don't have a

solution as our program will continue running and producing more output. We

convert n from a binary string to a number, and store the minimum we found so

far in best.

Otherwise we produce all permutations of 10 bits, which means counting to 1024.

If we have a valid_suffix we need to respect, we filter out values that don't

match the suffix. Next, we check if running a step of the program on these 10

bits produces the number we want. If so, we found the next 3 bits of our

solution, we recurse, looking for the next number (i + 1), setting the most

significant 7 bits of x as the expected suffix (x >> 3), then we prepend the

last 3 bits of x to the number we found so far (the math there just makes sure

we prepend it to n: ((x % 8) << (3 * i)) + n shifts the last 3 digits we

found enough to go in front of n).

This problem was fun, as I had to reverse-engineer the program to figure out an efficient way to search for the solution.

Day 18: RAM Run

Problem statement is here.

This one was easy. The first part is another maze traversal, very much like day 16.

The second part is also easy: we keep adding bytes to the memory one by one and check that the exit is still reachable. At some point, it stops being reachable and we found our solution. As long as traversal is efficient, it's no problem running it multiple times. Unlike part 1, we don't even need to find the shortest path, just whether the exit can be reached or not.

Day 19: Linen Layout

Problem statement is here.

Another surprisingly easy one. For part 1, the only gotcha is the input has much larger sequences than the example, so trying all permutations would take a long time unless we use memoization. Once we match a pattern suffix, we keep track of whether we matched it or not. With this, the solution is just a few lines of code:

matched = {"": True}

def match(pattern):

if pattern not in matched:

matched[pattern] = any(match(pattern[len(towel):]) for towel in towels if pattern.startswith(towel))

return matched[pattern]

print(sum(match(pattern) for pattern in patterns))

Here, towels is the list of available towels, and patterns is the list of

patterns to produce.

Part 2 asks us to count all possible combinations that produce a pattern rather

than just whether we can or cannot produce it. We can get this with minimal

modifications to the part 1 solution: we consider matching "" to be 1, and

instead of any(), we use sum() in the recursive function:

matched = {"": 1}

def match(pattern):

if pattern not in matched:

matched[pattern] = sum(match(pattern[len(towel):]) for towel in towels if pattern.startswith(towel))

return matched[pattern]

print(sum(match(pattern) for pattern in patterns))

This counts all possible combinations.

Day 20: Race Condition

Problem statement is here.

This was another surprisingly easy one. Since there is a single path through the maze without cheating, my approach was to first determine how far away each point that is not a wall is from the exit:

dist, at = {end: 0}, end

while at != start:

i, j = at

if (i - 1, j) not in dist and grid[i - 1][j] != "#":

dist[(i - 1, j)] = dist[at] + 1

at = (i - 1, j)

elif (i + 1, j) not in dist and grid[i + 1][j] != "#":

dist[(i + 1, j)] = dist[at] + 1

at = (i + 1, j)

elif (i, j - 1) not in dist and grid[i][j - 1] != "#":

dist[(i, j - 1)] = dist[at] + 1

at = (i, j - 1)

else:

dist[(i, j + 1)] = dist[at] + 1

at = (i, j + 1)

Traversal is easy: starting from the exit point, there should always be a single

not visited space we can go to next. Once we have this, the solution is easy.

For each (i, j) we can be on, meaning the keys of dist, we check if (i - 2,

j), (i, j - 2) etc. are in dist too (so all places we can get to in two

steps, ignoring walls). If any of the new coordinates are also in dist, we

check if we have indeed a shortcut: dist[(i, j)] - dist[(i + dx, j + dy]) -

2 >= 100. That is, the distance at (i, j) minus the distance at the end of

the cheat (i + dx, j + dy) minus 2 for the two steps we take while cheating

is greater than 100. Here, (dx, dy) is any of [(-2, 0), (0, -2), (2, 0), (0,

2), (-1, -1), (-1, 1), (1, -1), (1, 1)]. Counting these gives us all the

cheats:

shortcuts = 0

def cheat(i, j, dx, dy):

global shortcuts

if (i + dx, j + dy) in dist and dist[(i + dx, j + dy)] < dist[(i, j)] - 2:

d = dist[(i, j)] - dist[(i + dx, j + dy)] - 2

if d >= 100:

shortcuts += 1

for i, j in dist:

for (dx, dy) in [(-2, 0), (2, 0), (0, -2), (0, 2), (-1, -1), (-1, 1), (1, -1), (1, 1)]:

cheat(i, j, dx, dy)

Part 2 is not much more difficult. We can now cheat for up to 20 steps rather

than just 2. That means instead of the hardcoded list of (dx, dy) we

considered at step 1, we instead need to look for all coordinates (si, sj)

that are also in dist, with a Manhattan distance of at most 20 from (i, j).

I implemented a function that gives us all the candidates:

def candidates(i, j):

for si, sj in dist:

if si == i and sj == j:

continue

if abs(si - i) + abs(sj - j) <= 20:

yield si, sj

With this, we can update the algorithm from part 1 as follows:

shortcuts = 0

for i, j in dist:

for si, sj in candidates(i, j):

d = dist[(i, j)] - dist[(si, sj)] - (abs(si - i) + abs(sj - j))

if d >= 100:

shortcuts += 1

This will gives us all the cheats for part 2.

Day 21: Keypad Conundrum

Problem statement is here.

This was a bit tedious, but fun. It was the first one this year that took me a bit longer to solve. I solved this bottom-up, so there might be a more concise solution, but this is what I got: for part 1, I first represented the two types of keypads as graphs:

num_pad = {

"A": { "<": "0", "^": "3" },

"0": { ">": "A", "^": "2" },

"1": { "^": "4", ">": "2"},

"2": { "<": "1", "^": "5", ">": "3", "v": "0" },

"3": { "<": "2", "^": "6", "v": "A" },

"4": { "^": "7", ">": "5", "v": "1" },

"5": { "<": "4", "^": "8", ">": "6", "v": "2" },

"6": { "<": "5", "^": "9", "v": "3" },

"7": { ">": "8", "v": "4" },

"8": { "<": "7", ">": "9", "v": "5" },

"9": { "<": "8", "v": "6" },

}

dir_pad = {

"^": { ">": "A", "v": "v" },

"A": { "<": "^", "v": ">" },

"<": { ">": "v" },

"v": { "<": "<", "^": "^", ">": ">" },

">": { "<": "v", "^": "A" }

}

Note I used an edge-to-node representation. Then I wrote a function to computed all possible paths in a given graph between two nodes:

def paths(i, dest, result, graph, visited, path):

if i == dest:

result.append("".join(path) + "A")

return

visited.add(i)

for direction, next_i in graph[i].items():

if next_i in visited:

continue

visited.add(next_i)

path.append(direction)

paths(next_i, dest, result, graph, visited, path)

visited.remove(next_i)

path.pop()

The result is accumulated in the result parameter. With this, I generated all

possible paths between any two nodes in both graphs:

def map_path(graph):

path_map = {}

for k1 in graph:

for k2 in graph:

if k1 == k2:

path_map[(k1, k2)] = ["A"]

continue

result = []

paths(k1, k2, result, graph, set(), [])

path_map[(k1, k2)] = result

return path_map

num_pad_moves = map_path(num_pad)

dir_pad_moves = map_path(dir_pad)

The map_path() function generates all possible paths between any combination

of nodes. I stored the results in num_pad_moves and dir_path_moves for the

number pad and the directions pad.

The main gotcha of this problem is we can't brute force all possible

combinations of, say, going from 9 to 0 on the number pad, as each level

has, in turn, different ways to produce a working combination. This blows up

fast.

Also, the shortest path at one level might not be the shortest one at the next

level. For example, a path like <<< at the higher level pad translates into

navigating the lower level to < then pressing A 3 times. If the lower level

keys are further apart, the higher level requires more presses to get there, so

we also can't just look at the shortest path at the lower level to figure out

the best solution for the higher level.

On the other hand, I realized that once we do know at the next higher level how

to best get the lower level from one key to another, we don't need to recompute

that. So if, say, the second robot needs to get from < to >, the robot one

level above can always use the same optimal combination of key presses to get it

to do so. The search space for this is actually quite small. So I started with

the highest level, the best combinations of keys I can press to get the robot

one level below to go from any key to any other key:

best_moves = {

1: { (k1, k2): min(dir_pad_moves[(k1, k2)], key=len) for k1, k2 in dir_pad_moves }

}

These are the best moves for level 1, the robot right below. Then I implemented a function which, given a pair of nodes and a depth level, returns the best (shortest) combination of keys:

def sequence(k1, k2, depth, graph=dir_pad_moves):

best, best_len = None, 10 ** 10

for path in graph[(k1, k2)]:

if len(k := "".join(best_moves[depth][p] for p in zip("A" + path, path))) < best_len:

best, best_len = k, len(k)

return best

For each path we can take between nodes k1 and k2 in our graph, we look at

what is the concatenation of the best moves we can take at that level. We return

the shortest result. I'm prepending an "A" to the path here, as we always

start from atop the "A" key on any keypad.

Now we can use the best_moves for level 1 to populate the best moves for level

2, then do level 3 the same way:

best_moves[2] = {(k1, k2): sequence(k1, k2, 1, dir_pad_moves) for k1, k2 in dir_pad_moves}

best_moves[3] = {(k1, k2): sequence(k1, k2, 2, num_pad_moves) for k1, k2 in num_pad_moves}

Now best_moves[3] contains the shortest path (in terms of key presses at the

highest level) to go between any two keys. We can easily produce the value we

need from there:

total = 0

for code in codes:

result = "".join(best_moves[3][pair] for pair in zip("A" + code, code))

total += len(result) * int(code[:-1])

For part 2, I first thought of simply scaling out the solution to part 1 -

instead of computing best_moves 3 levels deep, do it 26 levels deep. This

should theoretically work, but it blows up the memory because we're dealing with

larger and larger sequences of keypresses. I realized we don't actually care

about the strings themselves, rather we just need the lengths for our result.

I modified the part 1 code to just look at lengths. best_moves is now

initialized with the minimum path length rather than just the path:

best_moves = {

1: { (k1, k2): len(min(dir_pad_moves[(k1, k2)], key=len)) for k1, k2 in dir_pad_moves }

}

sequence() now assumes best_moves contains lengths and returns a length

itself:

def sequence(k1, k2, depth, graph=dir_pad_moves):

best = 10 ** 20

for path in graph[(k1, k2)]:

if (k := sum(best_moves[depth][p] for p in zip("A" + path, path))) < best:

best = k

return best

Now we can scale out building best_moves up to 26 levels:

for i in range(2, 26):

best_moves[i] = {(k1, k2): sequence(k1, k2, i - 1, dir_pad_moves) for k1, k2 in dir_pad_moves}

best_moves[26] = {(k1, k2): sequence(k1, k2, 25, num_pad_moves) for k1, k2 in num_pad_moves}

With this, we can get the solution the same way we did in part 1. Note the same solution would've worked for part 1. Strings are not needed at all, it just took me until part 2 to realize this.

This was a neat problem. The part I found tedious was generating the keypad

graphs and computing the possible paths between nodes. But outside of that, I

really enjoyed it. Both parts had an aha

moment for me, which is my favorite

part of Advent of Code and puzzles in general.

Day 22: Monkey Market

Problem statement is here.

This one was very easy, as I was able to brute force the solution for both part 1 and part 2. For part 1, with the set up of multiplying, XORing, and modulo, I was thinking I'll have to derive some formula to speed up computation, but that wasn't the case. I got the results reasonably fast without having to do anything clever. I implemented this function to advance a number one step:

def step(n):

n = ((n * 64) ^ n) % 16777216

n = ((n // 32) ^ n) % 16777216

n = ((n * 2048) ^ n) % 16777216

return n

Then getting the result was straightforward:

total = 0

for n in nums:

for _ in range(2000):

n = step(n)

total += n

I was expecting part 2 will maybe introduce larger numbers (like instead of 2000 iterations, do 2000000) but no. I have a solution that runs in under 1 minute and gets the correct result. First, I updated the step function to also return the change in the least significant digit between the old value and the new value, plus 9 (more on the plus 9 below):

def step(n):

d = n % 10

n = ((n * 64) ^ n) % 16777216

n = ((n // 32) ^ n) % 16777216

n = ((n * 2048) ^ n) % 16777216

return n, n % 10 - d + 9

Then, for each initial number, I generate the next 2000 numbers, track the sequence given by the 4 changes, and the value we would get if the monkey would buy this sequence for this number:

buys, seq = {}, set()

for i, n in enumerate(nums):

buys[i] = {}

n, d1 = step(n)

n, d2 = step(n)

n, d3 = step(n)

change = d1 * 19 ** 2 + d2 * 19 + d3

for _ in range(1997):

n, d = step(n)

change = (change % 19 ** 3) * 19 + d

seq.add(change)

if change not in buys[i]:

buys[i][change] = n % 10

Since the first 3 numbers don't have a sequence (we need 4 changes), I hoisted

these out of the loop. That's the first 3 calls to step(). The change between

2 numbers can be any value between -9 and 9. If the previous digit is 9 and the

current one is 0, the change is -9. If the previous digit is 0 and the current

one is 9, the change is 9. Instead of keeping track of 4 different numbers, we

can encode the sequence into a single number. There are 18 possible values

between -9 and 9, so if we add 9, we get a number between 0 and 18. This way, we

can uniquely encode 4 digits as \(d_1 * 19^3 + d_2 * 19^2 + d_3 * 19 + d_4\).

I'm storing this in change. At each step, we get rid of the oldest change by

getting the modulo \(19^3\) of the value, then we multiply by 19 and add the new

change. If we haven't seen change before for this buyer, we store the last

digit of n in buys[i][change] where i is the index of the buyer, change

is the sequence.

After executing this, buys will contain all possible values for all possible

sequences for each buyer. As a small optimization trading off memory for speed,

I'm also storing all sequences we've seen in the seq set.

To produce the result, we can simply try each sequence from seq and add up the

values we get for each buyer:

best = 0

for s in seq:

total = 0

for i in range(len(nums)):

if s in buys[i]:

total += buys[i][s]

best = max(total, best)

Without the optimization, we can simply try all possible sequences, which is up to \(19^4\). It's a large number (130321), but not astronomical. With the optimization, for my input, we only need to try 40951 values.

As I said, this solves the problem in less than a minute. There's probably a smarter, faster solution, but brute force was good enough here.

Day 23: LAN Party

Problem statement is here.

This one was easy. For both parts 1 and 2, I represented the connections as an undirected graph. Starting with the connected pairs:

graph = {}

for pair in pairs:

if pair[0] not in graph:

graph[pair[0]] = set()

graph[pair[0]].add(pair[1])

if pair[1] not in graph:

graph[pair[1]] = set()

graph[pair[1]].add(pair[0])

Then for part 1, I generated all combinations of 3 nodes (using itertools) and

checked whether all 3 nodes are connected if one of them starts with t

:

total = 0

for group in itertools.combinations(graph.keys(), 3):

if group[0][0] != "t" and group[1][0] != "t" and group[2][0] != "t":

continue

if group[1] in graph[group[0]] and group[2] in graph[group[0]] and group[2] in graph[group[1]]:

total += 1

For the second part, I implemented a helper function that checks whether all nodes in an arbitrarily long group are connected:

def all_connected(group):

for i in range(len(group)):

for j in range(i + 1, len(group)):

if group[i] not in graph[group[j]]:

return False

return True

Then I simply generated all possible combinations, keeping track of the largest group:

best = []

for k in graph:

subsets = [combo for r in range(len(best), len(graph[k]) + 1) for combo in itertools.combinations(graph[k], r)]

for subset in subsets:

if all_connected([k] + list(subset)):

best = [k] + list(subset)

Day 24: Crossed Wires

Problem statement is here.

For part 1, I preloaded the values of x and y wires in a dictionary:

vals, gates = open("input").read().split("\n\n")

calc = {line.split(": ")[0]: int(line.split(": ")[1]) for line in vals.split("\n")}

Then I implemented a function to recursively compute the value of a gate:

def get_val(v):

if not isinstance(calc[v], int):

match calc[v][1]:

case "AND":

calc[v] = get_val(calc[v][0]) & get_val(calc[v][2])

case "OR":

calc[v] = get_val(calc[v][0]) | get_val(calc[v][2])

case "XOR":

calc[v] = get_val(calc[v][0]) ^ get_val(calc[v][2])

return calc[v]

If we already have an int in the dictionary, return that. Otherwise we

recursively get the value of the inputs. Then I loaded the gates into calc as

tuples of (wire, gate type, wire) - this is what get_value() expects.

for gate in gates.split("\n"):

expr, to = gate.split(" -> ")

calc[to] = expr.split(" ")

To get the final number, we start with all the z wires, reverse sorted, and

build up the result from there:

total = 0

for z in sorted(filter(lambda val: val.startswith("z"), calc), reverse=True):

total <<= 1

total |= get_val(z)

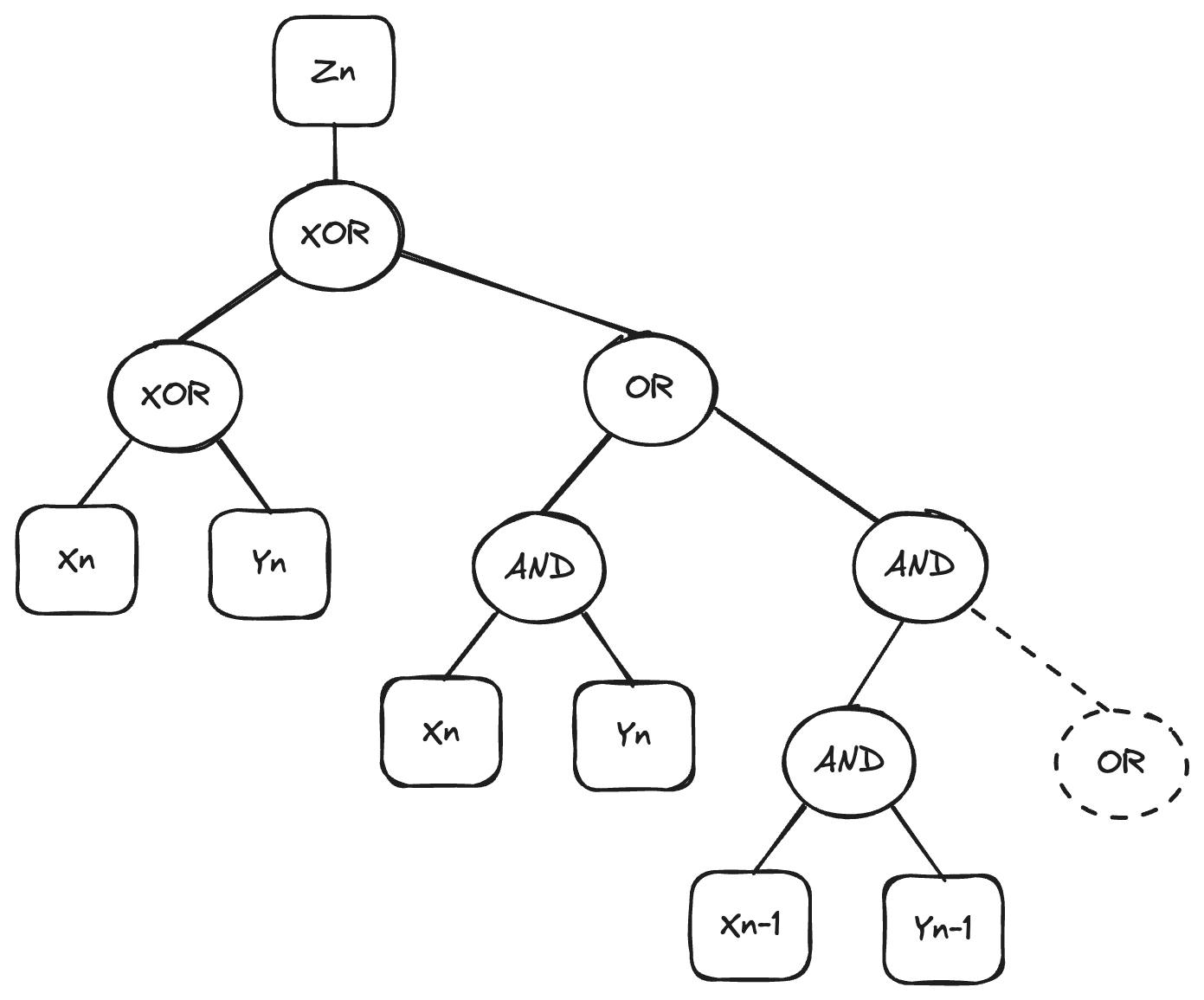

Part 2 was more difficult. This one took me longest to solve out of all problems in the event. In fact, I got to the solution doing some ad-hoc exploration, before I had an algorithm that produces it. The key observation was that for any \(z_n\), the wire configuration to determine whether it is 0 or 1 looks like this:

Realizing this, I solved the problem by checking whether the wires have the

right shape. For part 2, I represented the input wires x and y as their

names:

calc = {f"x{i:02}": f"x{i:02}" for i in range(45)} | {f"y{i:02}": f"y{i:02}" for i in range(45)}

The values don't matter in this part. Then the rest of the graph as tuples, this time ordered to make things easier:

for gate in gates.split("\n"):

expr, to = gate.split(" -> ")

calc[to] = sorted(expr.split(" "))

So the gate x01 AND y01 -> gcq would be represented as calc[gcq] = ("AND",

"x01", "y01").

I implemented a few helper functions. First one checks that for the given key, we have the exact operation between \(x_n\) and \(y_n\):

def op_n(key, op, n):

return calc[key] == [op, f"x{n:02}", f"y{n:02}"]

So op_n("gcq", "AND", 1) would return True. Then I implemented a couple of

search functions.

def find_key(value):

for key in calc:

if calc[key] == value:

return key

def find_subtree(root_op, op, n):

for key in calc:

if calc[key][0] == root_op and (op_n(calc[key][1], op, n) or op_n(calc[key][2], op, n)):

return key

find_key simply finds the key for a given value in calc. The second one is

more interesting: it looks for a subtree with the root_op operation at the

root, then either on its left or right branch, the op operation between \(x_n\)

and \(y_n\). This would help us find subtrees matching known shapes. For example,

if I know z05 starts with an XOR gate then one of its inputs is another

XOR gate for x05 and y05, I can retrieve the key z05 by calling

find_subtree("XOR", "XOR", 5).

Next, I implemented functions to check parts of the tree, making sure it has the expected shape. If the shape is not what we expect, we identified a swapped wire. Then we can use one of the above search function to find the right wire and correct the mistake. These checking functions either don't return anything, or return a pair of wires that should be swapped.

From the top, the function to check a z has the right shape is:

if n == 0:

if calc["z00"] != ["XOR", "x00", "y00"]:

return "z00", find_key(["XOR", "x00", "y00"])

else:

return

if n == 45:

return check_or(f"z45", n - 1)

z = calc[f"z{n:02}"]

if z[0] != "XOR":

return f"z{n:02}", find_subtree("XOR", "XOR", n)

if op_n(z[1], "XOR", n):

return check_or(z[2], n - 1)

elif op_n(z[2], "XOR", n):

return check_or(z[1], n - 1)

else:

if check_or(z[1], n - 1) is None:

return z[2], find_key(["XOR", f"x{n:02}", f"y{n:02}"])

else:

return z[1], find_key(["XOR", f"x{n:02}", f"y{n:02}"])

First we handle a couple of special cases. If n is 0, we don't have a carry,

if n is 45, we don't have an XOR at the root since \(z_{45}\) doesn't have

corresponding \(x_{45}\) and \(y_{45}\). Special cases aside, we check whether we

have an XOR at the root. If not, we have an issue here. We need to find the

subtree with two XORs.

If we do have an XOR at the root, we check whether the left or right branch is

XOR between \(x_n\) and \(y_n\). If it is, we move on to check the carry subtree

by calling check_or (implementation below). If it isn't we have an issue here.

We search for the correct subtree and return.

Using the same idea, we check the subtrees for the carry rooted at OR and at

AND:

def check_or(key, n):

if n == 0:

if not op_n(key, "AND", 0):

return key, find_key(["AND", f"x00", f"y00"])

return

if calc[key][0] != "OR":

return key, find_subtree("OR", "AND", n)

if op_n(calc[key][1], "AND", n):

return check_and(calc[key][2], n)

elif op_n(calc[key][2], "AND", n):

return check_and(calc[key][1], n)

else:

return key, find_key(["AND", f"x{n:02}", f"y{n:02}"])

def check_and(key, n):

if calc[key][0] != "AND":

return key, find_subtree("AND", "XOR", n)

if op_n(calc[key][1], "XOR", n):

return check_or(calc[key][2], n - 1)

elif op_n(calc[key][2], "XOR", n):

return check_or(calc[key][1], n - 1)

else:

return key, find_key(["XOR", f"x{n:02}", f"y{n:02}"])

Then to produce the solution, we check each z in turn, and if check_z

returns two key, we add them to our result, swap their values, and continue:

result = []

for i in range(46):

if (check := check_z(i)) is not None:

x, y = check

result += [x, y]

calc[x], calc[y] = calc[y], calc[x]

After running this, we end up with the 8 keys we need in result.

This problem was really fun, as I had to do a bunch of exploration of the tree

shapes and of the input to come up with the solution. This only works because

all the gates conform to this shape. I can think of wiring that would still

produced the desired result but not respect this shape, in which case my

solution wouldn't work. For example, introduce somewhere an OR node with one

of the input wires being a value XORed with itself. That wouldn't change the

evaluation result, as the value XORed with itself would always be 0, so

whatever the other input is, ORing it with 0 would keep it unchanged. That

said, it seems all inputs were shape-conforming so checking parts of their

subtree did the trick.

Day 25: Code Chronicle

Problem statement is here.

Without converting the keys and locks to numbers, we simply need to check if any

two schematics have a # in any one position:

def overlap(s1, s2):

for l1, l2 in zip(s1, s2):

for c1, c2 in zip(l1, l2):

if c1 == "#" and c2 == "#":

return True

return False

Here, s1 and s2 are schematics represented by arrays of strings. We don't

even care to separate the schematics into keys and locks, since all keys overlap

with each other on the bottom row and all locks overlap with each other on the

top row.

We check all pairs of schematics and count the ones which don't overlap to get our solution:

total = 0

for i in range(len(schematics)):

for j in range(i + 1, len(schematics)):

if not overlap(schematics[i], schematics[j]):

total += 1

I found this year's problems to be easier than prior years. The most difficult one for me by far was part 2 of day 24. The second one that took me a bit longer was part 2 of day 21. I was a bit disappointed that I was able to brute-force the solution to some of the later days. That said, it was all good fun. I always enjoy Advent of Code and hope the tradition continues for many more decades!